Cinephilia and Tsai Ming Liang

“This was an old write-up of mine when I used to put actual effort on my Instagram page @cinetasticc. I have always thought of writing it as a separate article because of the less readability and reach. “

Introduction

This article is dedicated to Tsai Ming Liang and his cinema. He is the filmmaker from whose films I have understood the “SLOW FILM” theory. I have slept many times watching his films. A Abbas Kiarostami quote which was referred to so many times in his film’s letterboxd reviews that:

“I prefer the films that put their audience to sleep in the theatre. Some films have made me dose off in the theatre but some films have made me stay up at night, wake up thinking about them in the morning, and keep on thinking about them for weeks.”

and I felt this quote taking a complete shape within Tsai Ming Liang’s world. The world in which your consciousness leaps in and you stay there for some time until you move on to the next filmmaker or other films. Tsai Ming Liang's films taught me so much about Slow Cinema (the contemplative contemporary cinema) and cinephilia in general, what it meant to him and what it meant to us. Before moving forward I want to credit Song Hwee Lim and his book “THE DIAGETIC WORLD OF TSAI MING LIANG” and will quote his book many times in this article. I would recommend everyone to read it after you experience some of his films and gain an immensely passionate perception of what a Tsai Ming Liang film is.

Slow Cinema

Before diving deeper it is important to know what is slow cinema. How does it work? Why do we need it? First and Foremost, Slow Cinema is not for everyone, we are living in an era where we can’t hold our attention for a minute, for some, it’s not even 30 seconds because of the reduced attention span and rise of commercial cinema with excessive use of continuity editing. Avenger (2012) had an ASL (Average shot length) of 3.16 seconds whereas Goodbye Dragon Inn (2003) had an ASL of 55 seconds. I personally didn’t get comfortable until I watched 3 films in succession. Thereupon the question is what attracts people to Slow Cinema?

Michel Cimen is one of the earliest critic to coin the phrase “a cinema of slowness” as he quotes “a cinema of slowness, of contemplation, as if they wanted to live again in the sensuous experience of a moment revealed in its authenticity.” What slow cinema outline is capturing the time and the moment, we seek what is now and not what’s going to be next. The famous term and title of his book “The sculpting of time” is I think what Tarkovsky refers to as cinema of slowness, of contemplation. Gilles Deleuze proposed in his two volumes of cinema a distinguishing factor between two types of cinemas (Classical cinema and modern cinema) for Deleuze, these two cinemas illustrate different modes of representing time. In the former, time “remains the object of an indirect representation in so far as it depends on montage and derives from movement images” in the latter, a cinema that emerged “with Orson Welles, with neo-realism, with french new wave ", it is the direct time-image, “a little time in the pure state” that “rises up to the surface of the screen”.

Asked in an interview about his notion of time, Tsai explained that he often felt, when he saw other people’s films, that “the time in them isn’t real enough, it’s either too short or too long”. He also talked about the ways in which his films differ in their relation to time: “So, for instance, in some films, to show that the hero has been waiting for quite a time you’ll be shown five cigarette stubs in the ashtray. Normally, for a scene like that I will film the character for as long as it takes him to smoke five cigarettes. That’s real time, but it’s very difficult to handle because the audience will get bored. But I think I do this deliberately because I want them to feel that the hero is in a state of anxiety, waiting for something that may not happen, etc. I don’t just want them to know logically that the hero has been waiting for a long time; no, I also want them to feel this real waiting time”

Boredom is a luxury

If Slow Cinema is not for everyone, then who exactly watches them? What is its market? The discourse and debate on cinematic slowness have been initiated mainly by film critics and editors who review and program films for a living and who, by nature of their work, are typically based in big cities, led a globetrotting lifestyle, and hobnob with directors and producers at these sites of exhibition and consumption. There is, hence, an undeniably metropolitan-cum-cosmopolitan outlook and privileged position that they bring to their taste in film. Also shared class and cultural background too plays a crucial role in understanding the slowness of cinema as what we are calling a slow experience after watching a Tsai Ming Liang film can be normal for a Taiwanese who resonates so much with the film's cultural background. It is the relationship among slowness, boredom, and spectatorship that will demonstrate the great divide in terms of the materiality of class, taste, and waste. Boredom, however, does not occur only when a film is “too slow” because “fast films can also bore." With regard to temporality, then, do audiences switch to a different time frame, so to speak when they enter the space of an art house cinema? Do they expect the pace of a film to be slower if they are watching an art film, bracing themselves for “boredom”? Can boredom, like slowness, be a pleasure that some audiences deliberately seek? According to Schoonover, art cinema “exploits its spectator’s boredom” by turning boredom into “a kind of special work, one in which empty on-screen time is repurposed, renovated, rehabilitated” We must relearn, according to Eriksen, “to value a certain form of time” that is slowness.

Nostalgic Cinephilia of Tsai Ming Liang

The endless debate and the recurring question about the death of cinema is not a phenomenon which we are facing currently but a time-long battle which has found its voice in the current age. But is it the cinema which is dying? No cinema can never die, it will be supplied in different forms, on different platforms but it won't die. Then what is it which makes us nostalgic and worried? Nostalgia, according to Sylviane Agacinski, is “a painful feeling of exile, the homesickness that the Germans call Heimweh, the feeling that wherever one is, one is not at home". The debate shouldn't be about the death of cinema but about the death of cinephilia. The Passion which used to keep some films alive. This whole article which is dedicated to a kind of cinema, a cinema of slowness is relevant because of that passion.

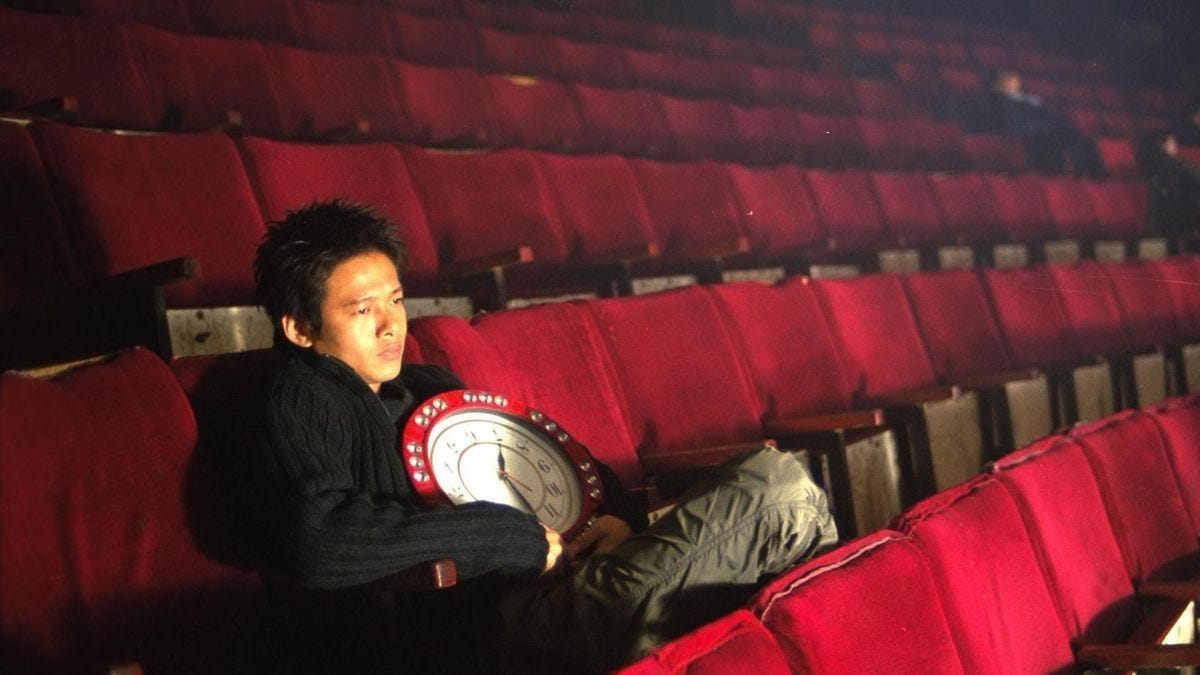

Tsai decided to make a film about the Fu Ho Theater, which was first featured in his oeuvre in a scene in What Time is it there (2001) after he found out that the cinema was due for demolition. Feeling a sense of loss having been reminded of the long-lost theatres of his childhood, Tsai opted to rent out the venue to shoot a film. Today, with it having just received a long-overdue Blu-ray restoration, Goodbye, Dragon Inn feels more powerful than ever. By lingering on the cinematic space it seeks to memorialize, Tsai’s long take challenges us to rethink the relationship among slowness, nostalgia, and cinephilia. By fixing a static camera in front of rows upon rows of empty seats, Tsai urges the audience to take a long hard look at the state of a decaying cinema and to reflect upon the material conditions that have brought about this state of affairs. Cast through the lens of nostalgia, the film reminds us that cinema belongs to a realm better known as a dreamscape, and that, for some, there cannot exist a life more meaningful than one spent watching films, talking about films, writing about films, and making films.